Volt Typhoon III

Welcome to Memetic Warfare. We’ll continue this week with a special post looking at the final Volt Typhoon report published by China’s CVERC. This post will be the direct continuation of the previous one, available below.

The continued exposure of Chinese cyber operations targeting US critical infrastructure has affected China’s strategic communications posture by putting China on the backfoot. The first two Volt Typhoon reports were unsuccessful in materially impacting public discourse regarding Chinese cyber operations, making a third report necessary. The CVERC thus published Volt Typhoon III on October 14th, 2024. The Chinese Ministry of Public Security, which oversees the CVERC, posted a statement noting the publication of the report on the same day.

Figure: Title Page of the Volt Typhoon III Report

While Volt Typhoon III has some changes, the pattern used by Chinese actors here is clear, as defined by Sentinel One’s Dakota Cary: “a cybersecurity company publishes a new report analyzing old leaked documents from the U.S. government, the CVERC picks up the piece and adds analysis–or in many cases, co-authors the report with the company–then state media regurgitate the report in English for international audiences.”

That pattern remains mostly true, but Volt Typhoon III exhibits signs of increasing sophistication. The CVERC translated the report into English, Chinese, German, Japanese and French, a new height of effort when compared to the previous two reports, which were published in English and Chinese. Volt Typhoon III is also significantly lengthier than its predecessors, clocking in at 59 pages compared to Volt Typhoon I and II, which were 15 and 18 pages, respectively. In comparison to the previous reports, Volt Typhoon III, while lengthier and multilingual, is lacking in other elements of polish; for example, the report lacks the CVERC watermark and shows lesser investment in formatting and design. This may indicate that Volt Typhoon III was not originally planned to be a part of the series but was added afterwards.

Volt Typhoon III further builds on the foundation of the reports that came before it. The abstract minces no words, doubling down on the claims made in Volt Typhoon II while attempting to damage US relations with European allies. After excoriating the US government, mainstream media, tech firms and other “liemakers” for keeping silent in the face of “ironclad” evidence, the authors claim that over 50 international cybersecurity experts contacted the CVERC to “express their concern” about the “U.S. false narrative” on Volt Typhoon. As per the report, the CVERC felt the need to release more “objective evidence” to disprove the alleged US information operation.

Figure: Volt Typhoon III Abstract

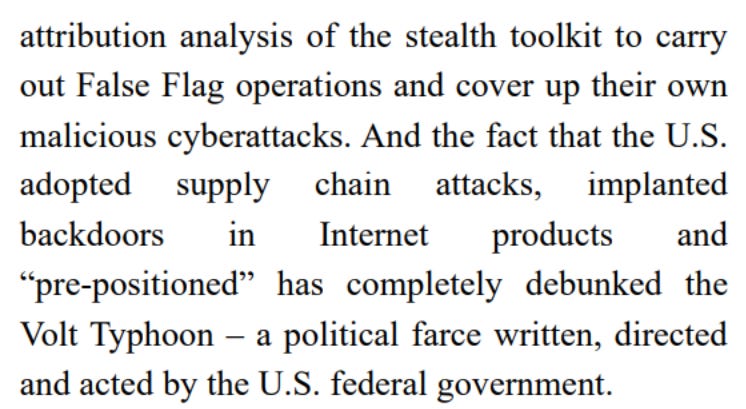

The following chapter, “‘Chameleons’ in Cyberspace”, plays on a recurring CVERC trope: analysis of NSA and CIA “cyber weapons”. The chapter focuses on “Marble”, CIA obfuscation software exposed by Wikileaks. Bereft of any references beyond screenshots of lines of code taken from Wikileaks, the report claims that the Marble toolkit not only obfuscates code to prevent forensics, but that it also has “shameless” function to insert strings in other languages, which the authors claim is meant to “mislead investigators and frame China…”. This alleged ability is what enables the US government to “act like chameleons in cyberspace”. Marble has been known since its original leak on Wikileaks, and has been discussed by mainstream media since.

Figure: Volt Typhoon III Description of “Marble”, referring to multilingual strings

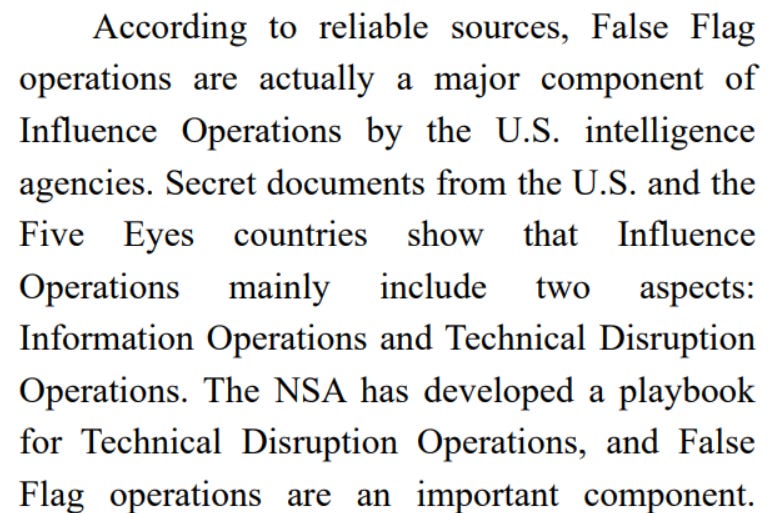

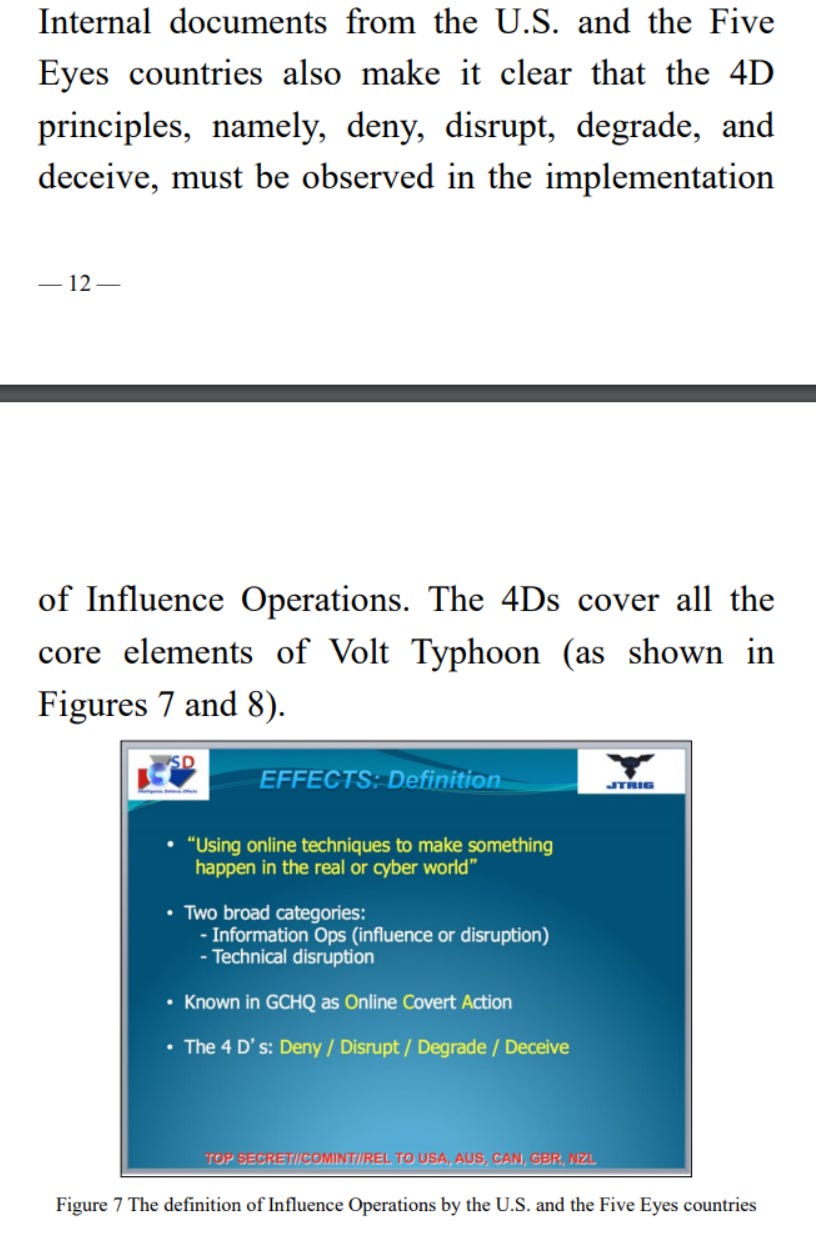

The CVERC doubles down on the false flag accusation, stating that “reliable sources” have informed them that false flag operations are a “major component” of US government influence operations. US influence operations, as described by leaked US and Five-Eyes documents, rely on “Information Operations” and “Technical Disruption Operations”, with false flag operations being a key component for “Technical Disruption Operations”.

Figure: Volt Typhoon III Description of US “False Flag” Operations

Volt Typhoon III then refers to documents from the UK’s GCHQ on Wikileaks to serve as the basis for the report’s claims. The authors use these leaks as purported evidence that the Volt Typhoon campaign is a “typical, well-designed disinformation operation( the so-called False Flag operation) in the interest of the U.S. capital group”. Furthermore, the first two Volt Typhoon reports served a purpose described in the concluding section of the chapter: they were meant to serve as an analysis of the “sinister plans concocted by intelligence agencies such as the NSA and CIA.”.

Figures: Volt Typhoon III referring to GCHQ documents describing influence operations.

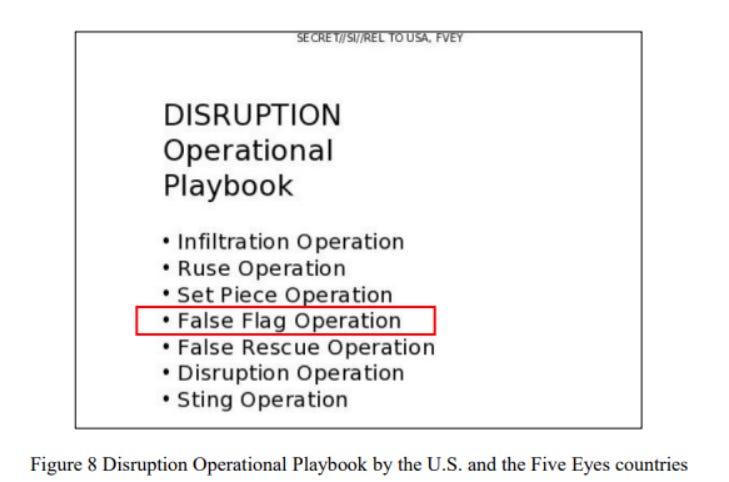

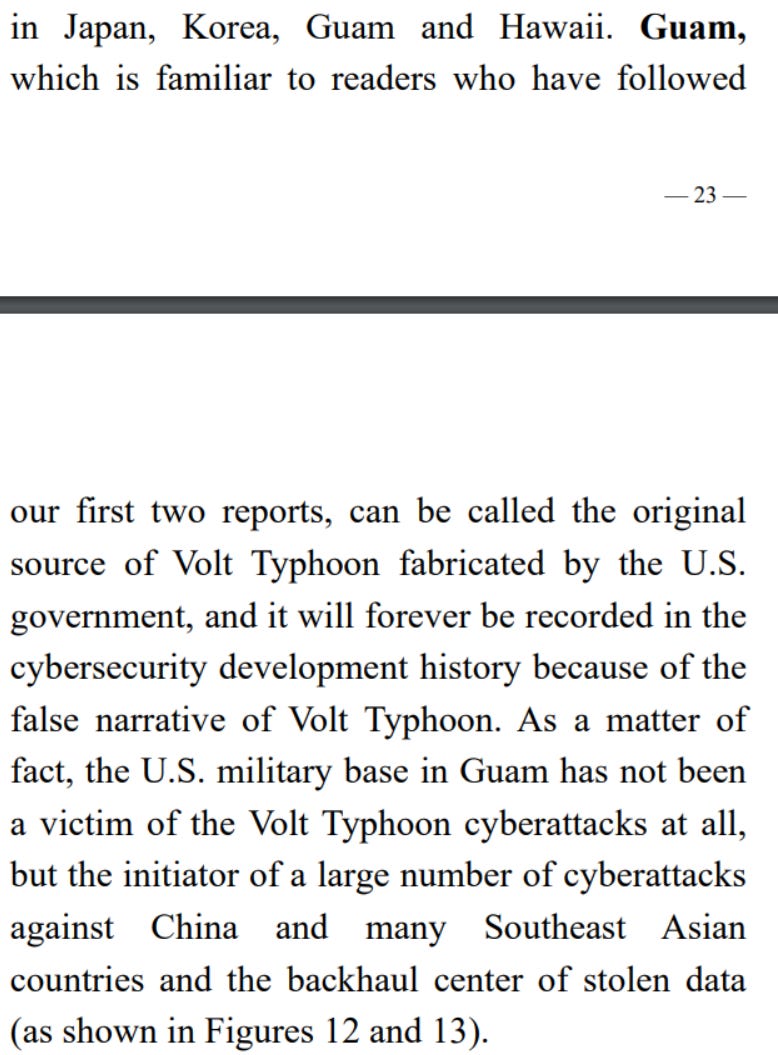

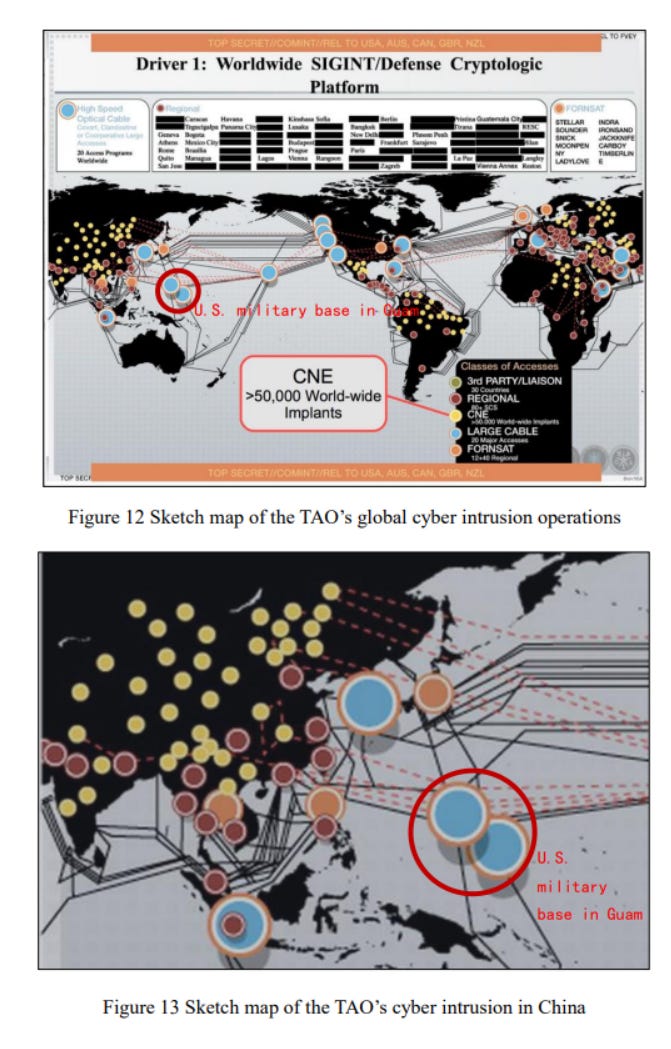

The next section, “‘Snoopers’ in Cyberspace”, repeats Volt Typhoon II’s claims about Section 702 of FISA. Similarly to the previous section and past CVERC publications, the section uses unrelated, leaked US documents as evidence. The section also covers previously exposed NSA projects, such as Prism, and regurgitates claims about the NSA’s TAO unit, claiming that they serve as evidence of alleged impropriety, but present them with no direct relation to Volt Typhoon. Guam, however, is mentioned specifically in a textbook case of deflection. US bases on Guam which Volt Typhoon targeted are accused, with no supporting evidence beyond screenshots of US SIGINT collection platforms, of having carried out “a large number of cyberattacks against China and many Southeast Asian countries”.

Figures: Left: Volt Typhoon III accusing US bases on Guam of “cyberattacks”. Right: Volt Typhoon III referring to leaked US documents as evidence.

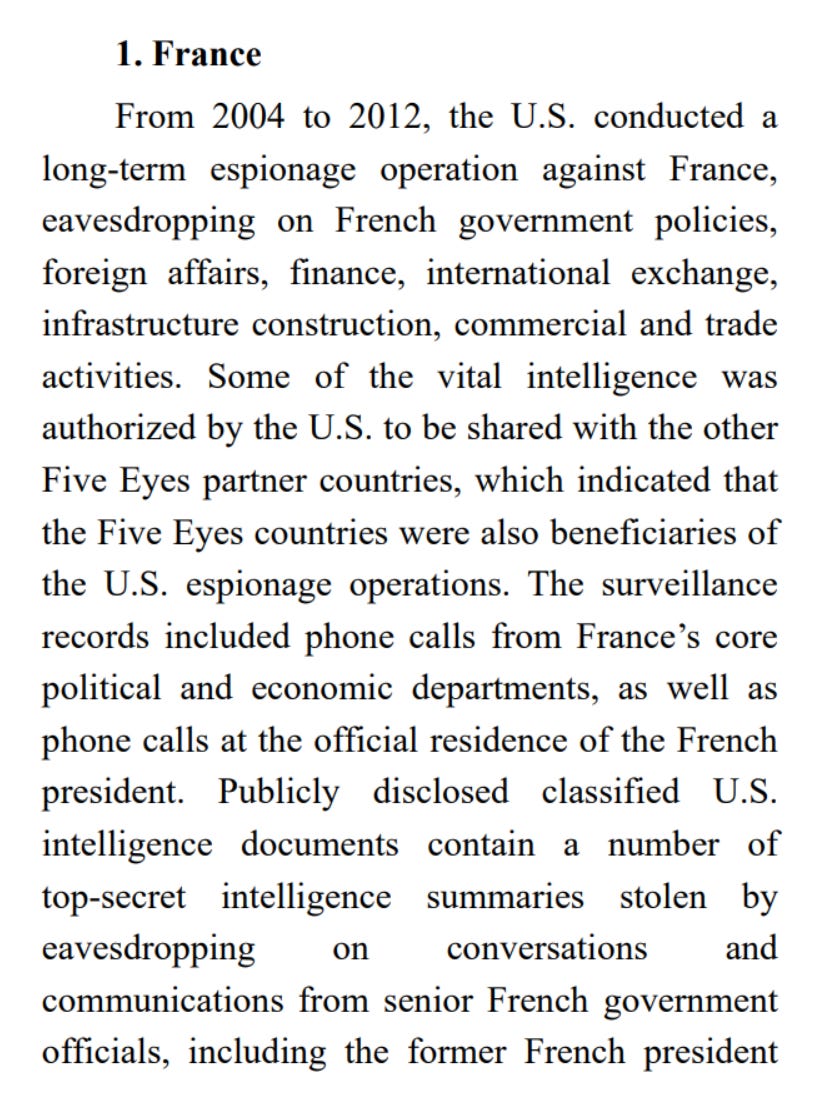

The fourth section, “‘Making Exorbitant Demand’ for Internet Intelligence”, describes previously exposed cases of US espionage against its allies. This chapter again recycles previously-exposed information exposed on Wikileaks, emphasizing US collection on US allies France, Germany and Japan in the previous decade. Each country is mentioned individually, with offenses described with references to Wikileaks and mainstream media mentions in an overt attempt to sow distrust between the US and its allies.

No previously unreported or new information is provided, and the section denigrates the US-EU Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework”, meant to regulate data transfers between the US and the EU as a way for the US to continue “wiretapping its European allies”. The section concludes by expounding upon the false claims that the Volt Typhoon II report made about Section 702 of FISA, claiming that “Ordinary U.S. Citizens” are the final group of victims purposefully targeted by the US government.

Figures: Volt Typhoon III sections describing historic US cyber operations and SIGINT collection on allied nations and US citizens

In an escalation against US officials, the report besmirches the former FBI director Christopher Wray, whom it claims is a “habitual liar” and was central to the “false narrative campaign”. This trend continues into section 4: “Demon behind Unusual Events”, which further launches unsubstantiated claims against US firms such as Microsoft, Open AI and Crowdstrike. The report’s conclusion retreads territory previously trodden multiple times. The conclusion section summarizes the main points and accusing the US government of running a false flag operation targeting China and coopting US firms along the way. The report concludes with a call from China for “normalized international exchange”.

Figures: Left: Volt Typhoon III criticizing former FBI Director Christopher Wray, calling him a “habitual liar”. Center: Volt Typhoon III claiming that the US intelligence community exerts undue influence over Microsoft in exchange for allowing it to enjoy a monopoly. Right: Volt Typhoon III Conclusion section.