MWW: As An AI Language Model Edition

Welcome to Memetic Warfare Weekly!

My name is Ari Ben Am, and I’m the founder of Glowstick Intelligence Enablement. Memetic Warfare Weekly is where I share my opinions on the influence/CTI industry, as well as share the occasional contrarian opinion or practical investigation tip.

I provide consulting, training, integration and research services, so if relevant - feel free to reach out via LinkedIn or ari@glowstickintel.com.

It’s great to be back after a busy work of training and consulting in Singapore, so we’ll be returning to our regularly scheduled programming more or less.

Anyway, let’s get this week going:

As An AI Language Model

The Indiana University Observatory on Social Media published an interesting report about an LLM-powered (in this case, Chat-GPT) social media botnet. Shockingly, this network was used to promote a crypto scam. How was this network detected? Searching the now infamous ChatGPT response, “as an AI language model”, on Twitter.

I’ve thought about the utility of powering accounts with NLP to enable them to post, engage in comments and conversation with other users online.

This vector is arguably much more difficult to detect and prevent at the content-level compared to AI-generated images and videos; individual posts are often short and can be finetuned to not go over a certain length, thus mitigating the chance of the posts being identified as AI-generated. Additionally, posts that are so short are hard to conclusively be identified as AI-generated, even by advanced models. False positives will also presumably abound.

What are the responses to this? Not clear yet. There’s no doubt that LLM providers will continue to invest in trust and safety and policy teams to develop methods to onboard clients, carry out KYC processes, develop algorithmic solutions and more, but this won’t be perfect.

Northern Guidestar

The New York Times’ investigation team, following on past work done by outlets such as New Lines Magazine, have investigated an international network of pro-China organizations centering around one individual named Neville Singham.

Many of the names mentioned both in New Lines’ work, but also of course in the NYT’s, are well-known to influence researchers and journalists, but very much in the political fringe of the US and Europe.

Historically, organizations similar to these have at best served as “useful idiots” as the phrase goes for authoritarian states, and in some cases - as is suggested by the NYT and other work here - are directly funded by actors close to certain states. For those interested in a great historical overview of this, check out Calder Walton’s review of Russian efforts historically, available here.

I don’t want to go over many of the specifics as I’d like to encourage everyone to read the article, but I do want to draw attention to a few of the investigative aspects of this article that led to its success.

The first is the importance of front activity for influence/information operations disinformation and propaganda. Too often, people in the field focus on algorithmic amplification, platforms and other online activity while forgetting that influence isn’t always online, and is often promoted or seeded by real people who must operate via registered companies, nonprofits or other organizations. Investigating people as nexuses of this activity can help map out disparate networks and contribute to attribution.

The next point is nonprofit investigation. Corporate investigation in of itself is its own field in OSINT, but nonprofits, NGOs and other organizations are often skipped. This is especially a shame for several reasons:

It’s easy (comparatively) to launder money via nonprofits, who receive donations from the wider public. This can also be done anonymously by say, foreign donors via other front organizations in many cases. Setting up an NGO and using it to launder money via donations, hire friends and associates to work there and more can all be comparatively easily done.

Nonprofits and NGOs are required, by law in most states, to make their internal financial documentation and information public via annual reporting, so we can see where money goes and comes from, and mostly - how it’s used.

Guidestar.org is a great starting point for this, but in many cases and as the NYT did, you’ll have to pull up specialized databases in every given country you wish to investigate. In the worst cases, you may have to physically go to a records office and pull records.

HalC2on Days

Halcyon has put out a fascinating report about the existence of a C2 Provider (command and control, meaning servers used as part of the infrastructure of a cyberattack; convey commands, exfiltrate data and so on and act as a proxy for the attacker).

Creating and operating C2 servers can be a challenge for threat actors. Standing up their own infra may result in them being easily exposed, blocked or even hacked back. As such, many choose to utilize commercial infrastructure - easy, affordable, scalable and harder to identify as being malicious.

Legitimate commercial server/infrastructure providers act to prevent their infrastructure from being exploited via multiple methods - internal scanning, KYC (know your customer) checks and more. These are infallible, so any provider understands that a percentage of its infrastructure can be exploited, but that’s just a fact of life.

Halcyon’s report provides indications that a commercial web hosting service named Cloudzy may in fact cater to a menagerie of global threat actors - primarily ransomware-oriented - by providing their commercial infrastructure to threat actors - making up tens of percent of their whole business.

The report does this by going through a number of interesting, and in one case innovative, investigative approaches - while noting that it is probable that the company is in fact aware of their infra being used for malign activity - it can’t be confirmed conclusively. Cloudzy isn’t necessarily required to carry out KYC checks of clients, and as such they can accept crypto to avoid interacting with regular financial institutions that do carry out KYC and onboard whomever they’d like without knowing a thing.

The company, believed to be Iranian in origin, attempted to obfuscate its true origin and used proxy corporate registration services in the US to avoid providing information as to its true provenance, in addition to not having any actual presence in the US. Further investigation indicates that most employees are based in Tehran, employed by an Iranian firm and that many Western or American employee accounts on LinkedIn appear to be fake or use Western names for Iranians.

The main relevant finding for the report in terms of investigation is the innovative use of RDP hostnames. Cloudzy provides its VPSes (virtual private server) to clients in exchange for cryptocurrency, and lets them access them via Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP).

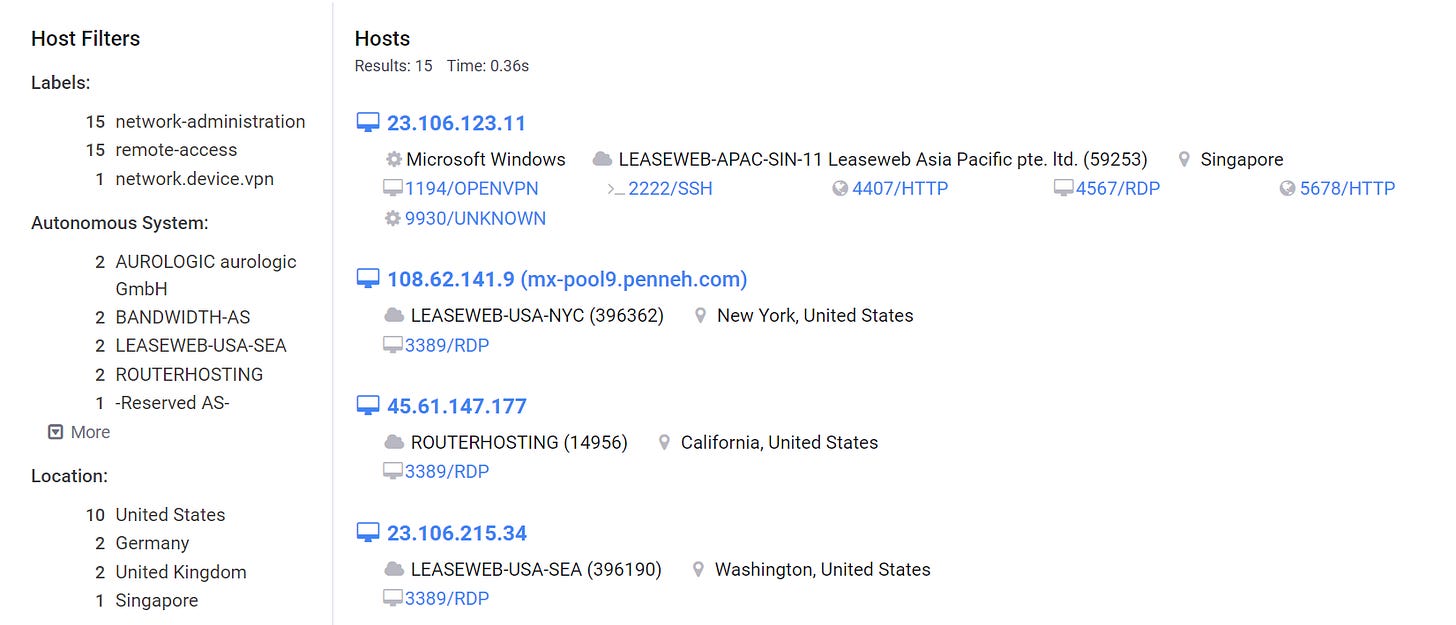

There’s more detail in the report, but essentially - the same hostnames that appeared in forensic work of known hacks are visible on Cloudzy servers - see the below table.

Looking up DESKTOP- 1H40CJO on Censys retrieves other hosts, including those not hosted by Cloudzy, that may be suspicious based upon open ports, services and other information.

This, in my opinion, is one of the main takeaways of the report. Anything unique, or even semi-unique, can be pivoted upon both in cyber threat investigations, OSINT in general or any other kind of subfield. Keeping our eyes open to any seemingly anomalous or unique datapoint is crucial to succeeding, followed only by then knowing how to take that datapoint and pivot.

This is especially relevant as threat actors increasingly utilize commercial infrastructure for malign cyber activity. However, it doesn’t stop there. Any sort of illicit online activity - IO, cybercrime or otherwise - can utilize and exploit commercial infrastructure, and developing technical skillsets to exploit unique datapoints in each specific field is still needed, especially in IO.

Lastly, the point remains that any kind of investigation into any kind of online activity requires knowing a few fields. This investigation couldn’t have succeeded without OSINT and people investigation skills, company registry and financial investigation knowledge, and of course - deep domain expertise in cyber threat investigations, malware analysis and more. This may seem obvious to many, but in reality it’s much harder said than done, and it’s unfortunately often difficult to get CTI analysts to really adopt the full OSINT mindset.

That’s it for this week - we’ll get back to doing some more practical guides in the coming weeks. Thanks for reading!