Insane in the Meme-Brane

Welcome to Memetic Warfare.

My name is Ari Ben Am, and I’m the founder of Telemetry Data Labs - a Telegram search engine and analytics platform available at Telemetryapp.io. I also provide training, consulting and research so if you have any specific needs - feel free to reach out on LinkedIn.

This week’s post will be dedicated to a monumental Reuters investigation into a US-orchestrated influence operation. We’ll talk about the operation itself, what led to it, why it was misguided and presumably ineffectual, what could/should’ve been done and make some jokes on the way.

Insane in the Meme-Brane

Reuter’s Chris Bing and Joel Schechtman have published what can only be described as a bombshell of an article. They also were the first to publish on US IO targeting China in 2019, available here.

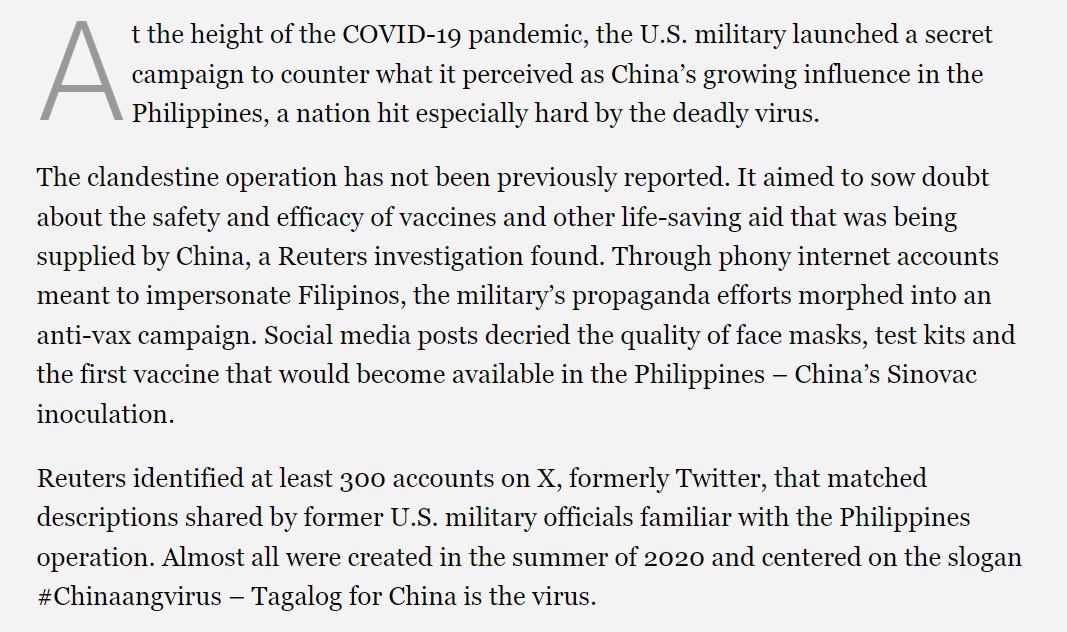

Check out the BLUF below:

The operation saw but two springs from early 2020 to mid 2021. The IO staked out some spicy positions, including promoting contentious claims about alleged pork gelatin.

We’re in some unprecedented area regarding American and Western influence activity. I’m in favor of Western states carrying out IO ethically, but public health should be off limits most of the time, if not all of the time.

This is a big deal to say the least, but we also shouldn’t freak out completely over it.

For those concerned, this was only enabled by now (partially) rescinded Trump-era powers granted to the military. Apparently the operation has been investigated and audited internally and hopefully the requisite lessons will be learned.

While the ethical concerns can be handled and remediated with reforms and guardrails, what’s equally concerning is the lack of strategic foresight and planning.

Why carry out an operation that actually runs counter to American interests?

Mitigating the impact of the coronavirus pandemic would have been much better for American interest than just taking the opportunity to dunk on China, and the exposure of the operation is a serious stain on American credibility in the region. Suffice it to say that Chinese mouthpieces are already on this.

Let’s review what led to this being carried out.

The Pentagon set up the operation apparently as a response to China’s attempt to shift blame for the Coronavirus to the US:

This was exacerbated by lacking American efforts to actually win over hearts and minds:

There’s no way to know how effective the operation was:

Personally I’m not so sure about the correlation here between the IO and the unwillingness of Filipinos to jive with the jab. There are often multiple other factors at play, and the operation probably wasn’t super effective.

Let’s also bring up the inevitable exposure of any successful influence operation. Success in IO means reach, and reach means a much higher chance of attribution (especially if amplified by a large online network, providing a larger attack surface for OpSec breaches and attribution).

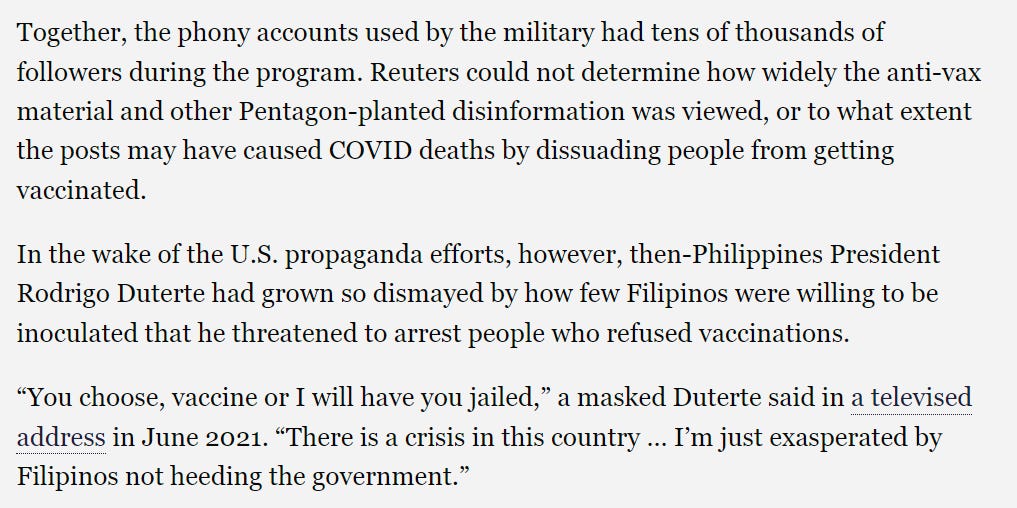

As Rid brings up, there was a lack of foresight about the implications of exposure. This is the kind of thinking that one may expect from a military, but is actively detrimental to the US’ global influence efforts. As we see below, not everyone was on board.

The article also provides us with some insight into the inter-department bureaucracy and dynamics between the DoD and the State Department. Apparently, the operation was shared with US diplomats, who objected to it:

We get some incredibly detailed findings later on in the article on the specific officer who pushed for the operation:

His approach wasn’t shared by everyone as stated:

Notably, the impact of Trump appointees here is also apparent. Esper’s decision to enable military officers to bypass the State Department for “psyops” seems to have been what enabled this operation:

Let’s look at some content.

The operation was expansive and extended beyond the Philippines to southeast Asia and beyond:

There was cross-platform activity on Twitter, Facebook and more, with some of the accounts being of initial higher-quality than say China (note the ethnically-accurate names, the username not being some auto-generated alphanumeric string and so on.

The operation was halted a few months in to the Biden administration:

How was the operation attributed? Twitter apparently used IP address and browser session information to identify over 150 accounts. OpSec is hard my guys, but this could have been avoided.

Meta also identified Facebook and Instagram activity, unsurprisingly:

Much of the operation was contracted out:

They’re still out there doing their thing and failing upwards:

At the end of the day, the DoD reached the right conclusions:

There are now reasonable guardrails in place to ensure that these sort of shenanigans don’t happen again, and I give the Pentagon credit for being willing to discuss this to some degree.

Not to say that they won’t, but I’m sympathetic here. It’s not easy facing an adversary who isn’t overencumbered by morals and scruples, and the overly gung-ho attitude at first will eventually be refined into something more effective.

So, for all of the blood, sweat and tears put into this, what’d the US get out of it? Well, in the Phillipines, not much.

The Philippines operation was the main focus of the article and seems to have been a focal point of the operation.

In hindsight, this was probably one of the least-warranted IO campaigns in recent history, as PH-China relations are at a historic nadir.

Apparently a strong majority of Filipinos view China as their “greatest threat” thanks to China’s maritime territorial claims, irrespective of any American influence operations.

That’s not to denigrate the effort at the time.

When the operation began, Duterte was still president. No one was quite sure how he’d take the Philippines going forward in relation to China. Duterte also readily purchased Chinese vaccines with an open hand (understandably, it was much needed and it wasn’t easy or even possible to acquire others).

Not only was this sort of operation unwarranted, but it’s of course being pounced upon by Chinese state media, influencers, and covert online assets.

One image and narrative, promoted by a prominent pro-China mouthpiece, has tens of thousands of views at the time of writing, and many other examples abound, some hitting tens or even hundreds of thousands of views.

To say the least, this operation was ineffective and has already/will empower Chinese influence efforts.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs had an expected but somewhat muted response as of the time of writing, as presumably they’re still working on their media campaign:

The Global Times was only able to get a lackluster tweet with a reused caricature out on the 16th:

As an aside, this really shows the power of the “decentralized” influencer network. Multiple guided but day-to-day independent pro-China influencers can take the reins and rapidly respond to and exploit surprise scenarios. State media outlets, however fast they may be, will still take longer to get something higher-quality out.

Let’s move on. So we’ve determined that this operation was a huge mistake: ethically, practically and in essentially every other way.

In some ways, this should be reassuring, being skilled in IO or other below-threshold activity takes time and effort. In all honesty, it’s an odd place for any democratic state, let alone the world’s leading democracy, to be active in, and we should probably be thankful that the US isn’t naturally skilled in it.

That isn’t to say that the US and allies won’t get better at IO, they will. It’ll take time for the US to do so and operate both practically and ethically.

Some points that we’ve discussed in the past:

The US needs to professionalize its IO corps, and not rely on expensive contractors to set up WordPress sites and Twitter accounts with poor OpSec.

Guidelines on ethics are needed for everyone. Ethnic and religious elements should be considered VERY seriously prior to any operation.

Some topics, such as global pandemics/healthcare/vaccines should be off-limits for covert activity of this nature.

Holistic IO is better. The military/DoD shouldn’t be running most “psyops” by themselves, and they’d be better served by collaborating with other departments.

There are some other points that are worth bringing up.

The military officer mentioned, and perhaps other in the military/DoD, are interested in expanding their purview from targeted “psyops” of military value to much, much broader coverage of influence.

This is a a lofty goal.

To maximize shareholder value and scale cross-functionally, the military and its contractors turned to the traditional networks of inauthentic accounts/entities and domains approach.

The downsides of this approach are manifold: it rarely works, it costs a ton, and it has a high risk of exposure, and is frankly a bit derivative.

Why do I bring this up? Well, we’ve seen DoD/Military affiliated operations like this in the past as well, such as the “Unheard Voice” network.

These differ from other operations run by other branches of government. Sophisticated Western operations, such as potential hack and leaks (as well as other things that we aren’t necessarily aware of) are presumably carried out by intelligence agencies or other offices.

Military efforts, by comparison, are often lacking. This isn’t unique to the US - look at the French military’s operation in Mali.

This could be due to multiple issues, including a lack of experience being Extremely Online, an even more restrictive hierarchy, a reliance on contractors for anything that isn’t a core responsibility of the military, or any number of other reasons.

Looking forward, I wouldn’t be surprised if we eventually see more inter-agency coordination of influence activity, similarly to cyber activity. It’ll take the US time, but I’m sure that as we slide into a new normal of global competition that we’ll see an improvement in capabilities and ethics over time.

There were alternatives, such as running solely public diplomacy/Stratcom campaigns, selectively hacking and leaking, and others.

None of the above are perfect, nor would any have necessarily been successful. Selective and ethically-done hack and leaking could have been useful in some capacities, but the others are a bit of a crapshoot.

Personally, this situation to me seems to scream for effective overt messaging and StratComs, but that’s just me.

Here’s to hoping that further American investment in global influence (not a bad thing in of itself) will be carried out more ethically, professionally and effectively.

If you’ve made it this far, then I’d like to thank you for reading. Feel free to let me know what you think and check out Telemetryapp.io.