Habemus Viginum

Welcome to Memetic Warfare.

We’ll start off by reviewing Viginum’s latest report on “Storm-1516”, which has interesting timing considering France’s latest stratcoms offensive against Russia.

I personally still refuse to accept the Microsoft naming convention as it’s just harder to track than something with a more unique name, like CopyCop, so it’s a bummer to see it becoming the standard.

Regardless of my thoughts on Microsoft’s naming convention, it’s great to see Viginum put out an in-depth profile on one threat actor, and I hope that see more of this type of reporting going forward. I’ve covered Storm-1516 and CopyCop in-depth here in the past and in other venues, so I won’t rehash their activity here.

Viginum always puts effort in CTI-ing their reports, giving it a TLP and some relevant aesthetic choices:

Summary below for those who want it and won’t read the whole report:

A few things pop out to me immediately:

Viginum has identified 77 operations, and they even include a list of them at the end - kudos to them, really. Adding the entire list of instances is huge and something that I hope others do.

There’s an open question here as to how Viginum views CopyCop. CopyCop is the Recorded Future (and better IMO) name for Storm-1516, run by John Mark Dougan. Viginum here apparently sees them as separate yet overlapping and as this cluster having closer ties to the R-FBI. I’d be curious to see how Viginum describes the nature of relations between the actors here.

I like the attribution of a potentially-affiliated GRU officer here as well, that’ll be a rich pivot point for others to investigate.

Moving on, the report covers their past activity, and does bring up an interesting discussion point re a specific domain impersonating the French Ensemble and the overlap between operators of CopyCop and Storm-1516:

There’s also some standard coverage of their use of deepfakes, AI and so on, and more interestingly - the use of forgeries:

While up until this point the majority of the report has been the standard coverage of past activity, it gets really interesting in section 3 where the authors visualize the cross-organizational distribution chain:

We’ll skip ahead then over their discussion of dissemination to attribution to Russian actors, including another solid chart describing the complex operation behind teh scenes:

There’s a lot more here on these people and organizations, so read it if you’re interested, but we’ll move on to the next section. It’s not often that I say this, but the appendices are very well done and contribute greatly - just check out the list of attributed operations:

There’s a lot to pivot on for domains:

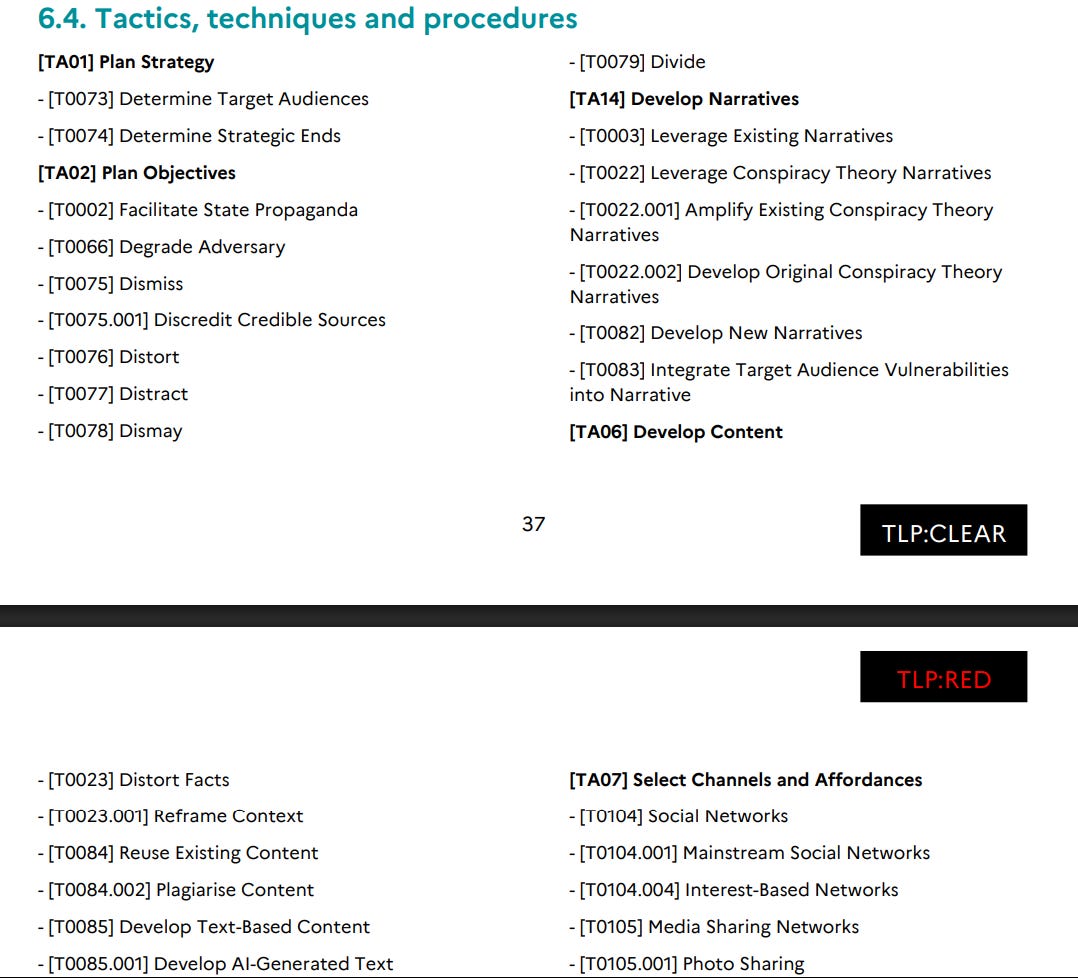

There appears to be a slipup in the DISARM framework section, with one page labelled TLP:RED. As an aside, I always complain about DISARM not being useful - just look at the below TTPs and you’ll see what I mean. I mean, guys, come on - “Distract”, “Dismay”, “Develop New Narratives”, “Determine Strategic Ends” - this isn’t useful.

It doesn’t improve in other sections - DISARM Red still has a lot to do to become useful, and I’m not convinced that it ever truly could be:

Overall though - some great stuff, and I’m glad to see it. The counter-IO industry has experienced a bit of a downturn lately with fewer publications and research being put out by companies, so I imagine that we’ll all be relying more on Viginum and other agencies for interesting research in the near-ish future.

The next topic that we’ll get into takes a look at North Korean IT workers yet again. Kraken, a crypto investment platform, ran a honeypot operation after they identified a suspicious interviewee and published a report on it, available here.

The report itself is very, very interesting and beyond the CI implications for companies, there are some interesting things to consider here for IO/cyber.

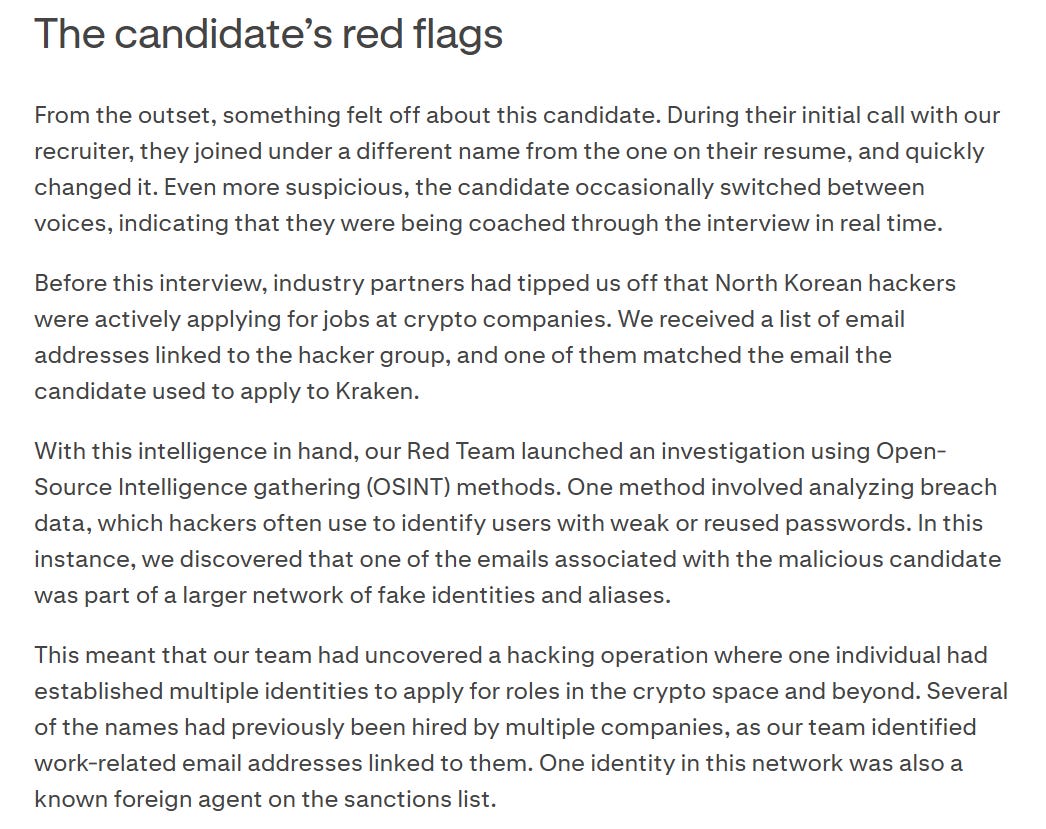

The first point to consider is how Kraken identified the interviewee as suspicious.

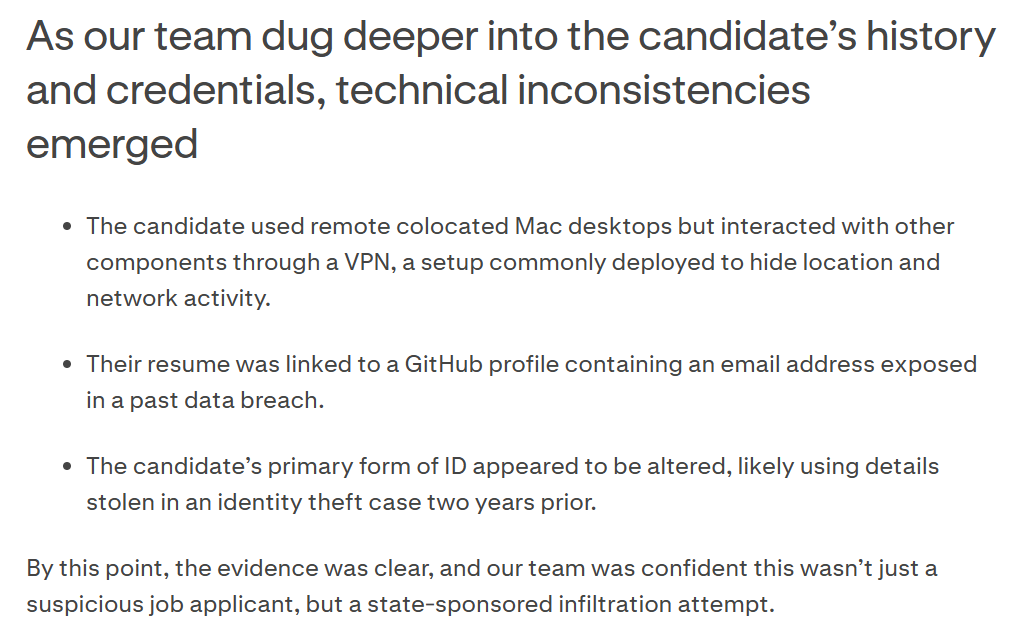

Industry information sharing provided the initial lead, and then Kraken used breached data to look up the email address that the interviewee used, seeing that it was exposed in past breaches meaning that it could have been taken over. The interviewee also used another email for a Github account and used some gen-AI altered documents:

Platforms also often used breached data for similar purposes, but breached data can be used as well to see if an email address or phone number is legit or not. If an identifier appears in multiple historical leaks that jive with the background of the account being created or person applying, that data can also be used to assess authenticity - after all, who hasn’t been in a breach or two.

So, there are also lessons here for advanced methods for preventing infiltration and combatting misuse of a platform - looking for breached data to confirm authenticity or find exposed assets, sharing information and so on. All of this is applicable for both defensive and offensive IO - how to create assets/prevent the creation of assets on various platforms.

There’s more though.

Interestingly enough we get visions of what may come in the future of combatting platform exploitation from the gaming industry. TechCrunch had an interesting look at how Riot Games is combatting cheaters on its platform by using hardware fingerprinting as well as virtual HUMINT:

They’re willing to even do selective disclosure intelligently - a lesson for others:

There’s more though - there’s even an element of psychological warfare here, which I found to be fascinating.

The last piece is hardware fingerprinting:

There are many lessons here.

Firstly, using these asymmetrical and unusual methods (from an official organization) to counter cybercrime may well be more effective than traditional enforcement mechanisms.

There are many lessons in that for government agencies seeking to combat cybercrime or IO internationally - you can’t operate in the same fashion, you have to work asymmetrically and in new, creative ways to mitigate risk.

Secondly, a combination of proactive investigation and infiltration is key. Defensive work can never just focus on a given asset, and will always have an offensive component. Imagine if Riot Games were to go a step further here and not only selectively disclose some anti-cheat information, but were to do so with a cheat that provides them with telemetry on cheaters - think about Sophos’ recent report in which they monitored Chinese activity for years.

Thirdly, creativity is effective. Using humor and trolling as well as doxxing even can be useful when working against cybercrime, even if it isn’t useful in combatting nation-state threats who don’t care.