Guest Post: Hash Slinging Slasher

Welcome to a special guest post of Memetic Warfare! My friend and colleague Max Lesser recently did some great investigative work at the FDD and had more details to add, so see below. Give him a follow as well on the FDD site as he always puts out great stuff.

Guest post begins below:

My name is Max Lesser. I work with Ari at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD). Today, I am sharing an investigation I worked on with one of our fantastic interns. Reach out to me or Ari if you are looking for new talent. We highly recommend her.

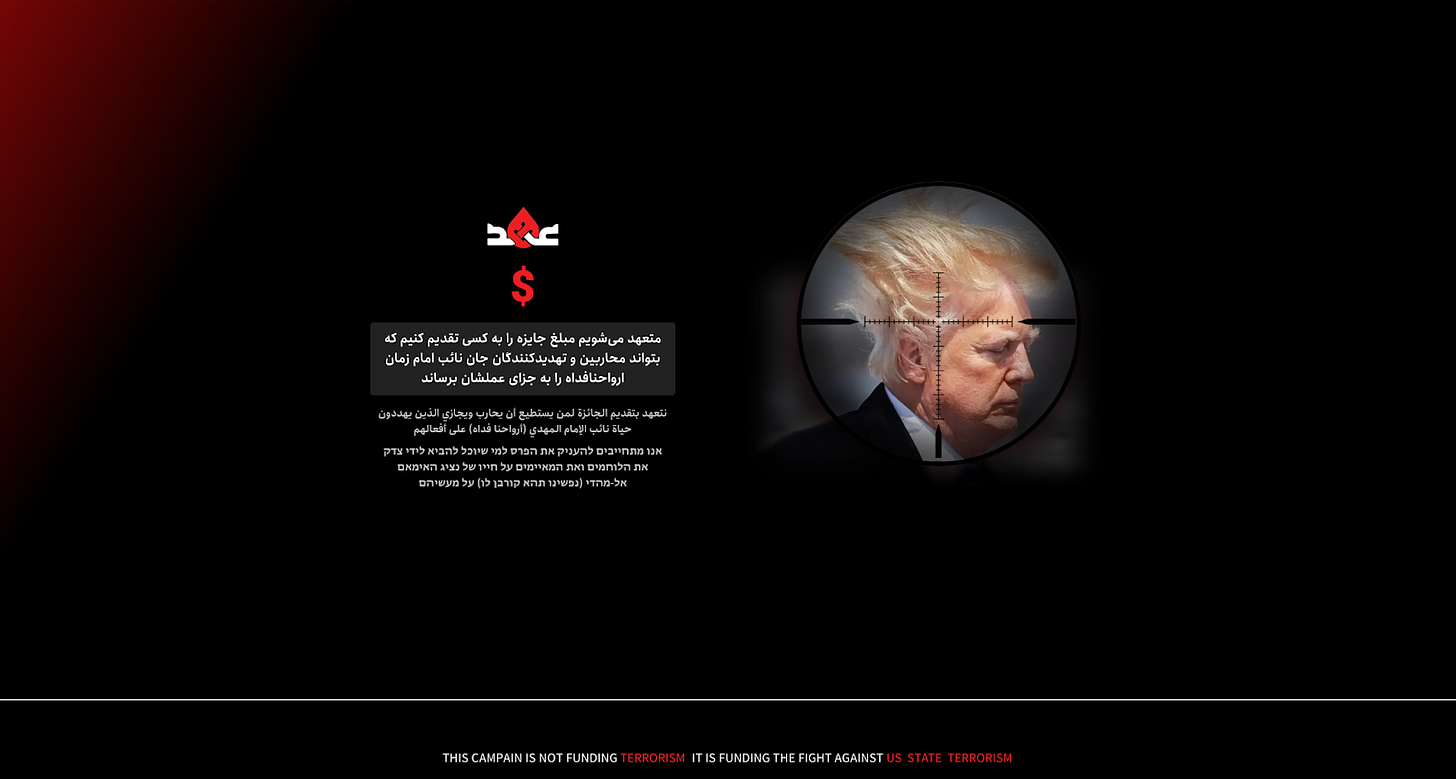

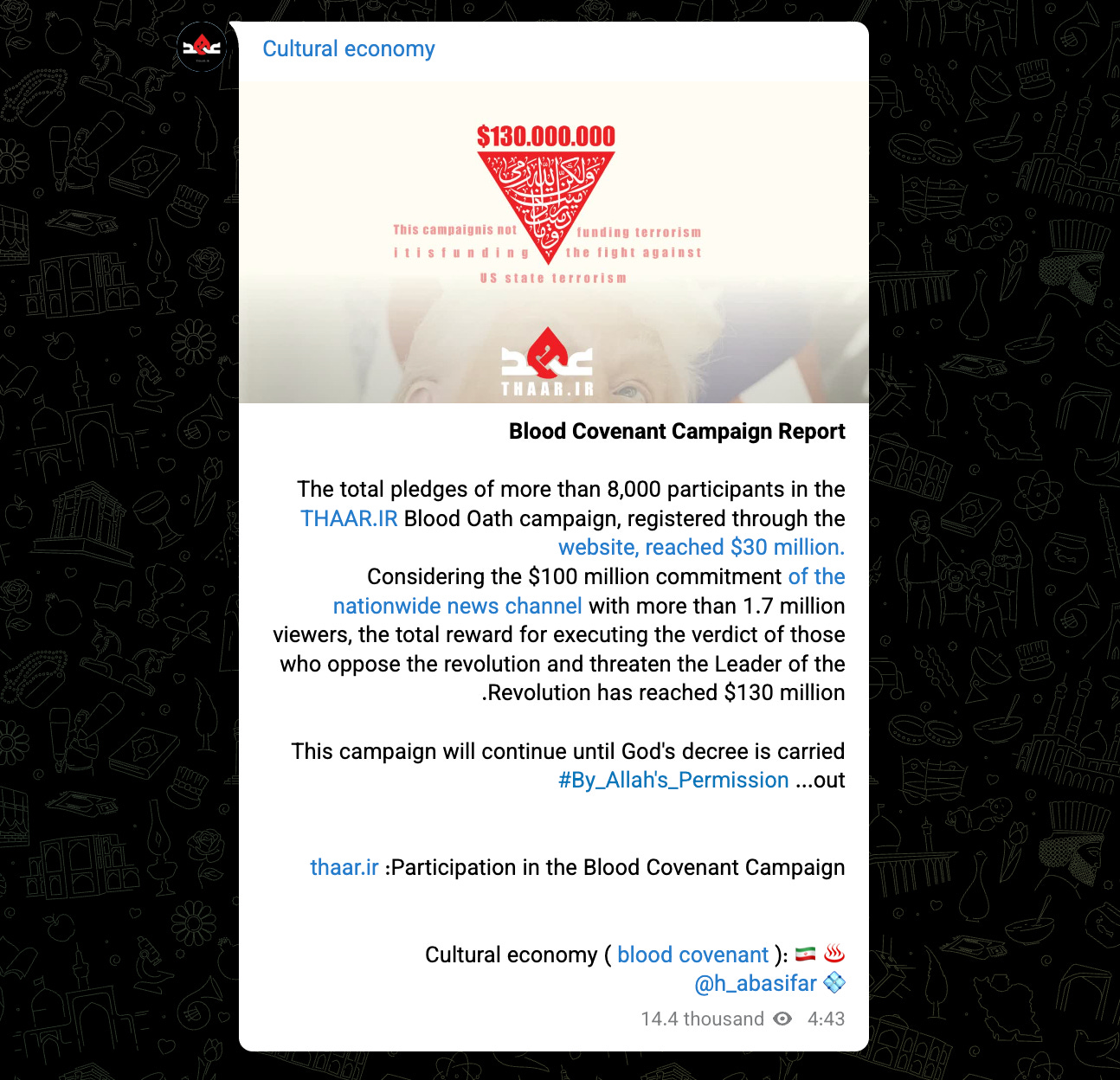

We first became aware of the website thaar[.]ir on July 8 after our intern came across it while “doomscrolling” on Twitter monitoring for malicious Iranian activity. The site, which has seen increasing news coverage over the past few days, allegedly has been crowdfunding a bounty for Trump’s assassination. It first appeared in DNS records on July 2, shortly after one of Iran’s top Shiite clerics issued a fatwa for Trump’s assassination on June 29.

Figure 1. Thaar[.]ir homepage as of July 8, 2025.

We then conducted a technical investigation into the website – as well as open-source intelligence (OSINT) investigation to identify related emails and social media profiles – that uncovered a man involved in the website’s creation, Hossein Abbasifar (حسین عباسیفر).

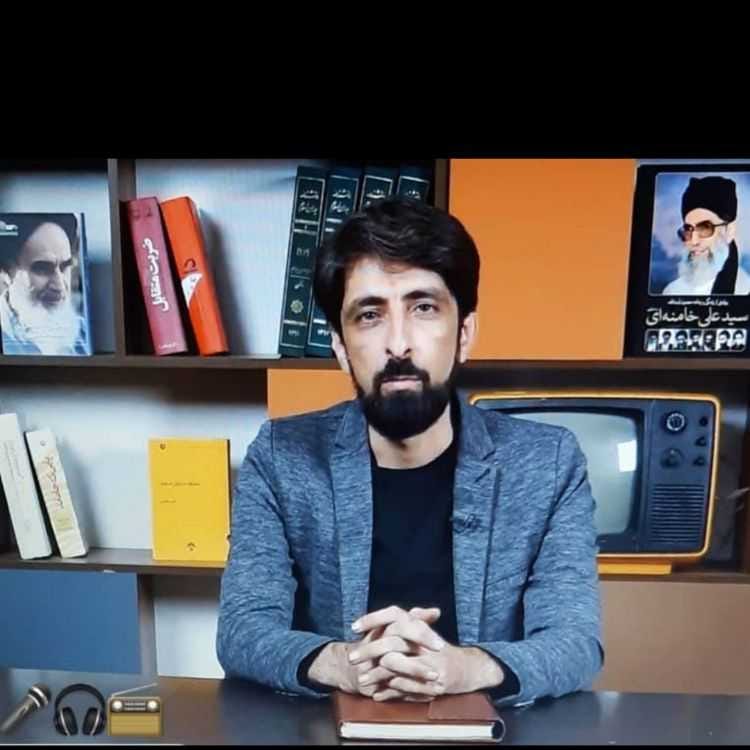

Figure 2. Profile image for Hossein Abbasifar’s Skype, showing him in front of photos of Islamic Republic founder and first Supreme Leader, Ruhollah Khomeini (left), and his successor, Ali Khamenei (right).

Here’s a step-by-step overview of how we unmasked Abbasifar.

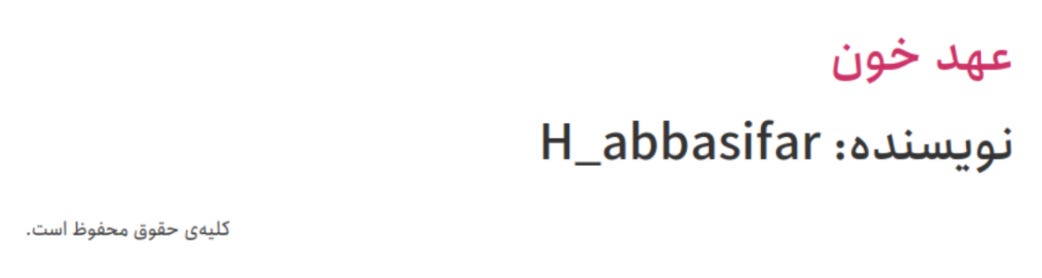

First, we observed that thaar[.]ir uses WordPress, an open-source content management system (CMS) used by millions of websites worldwide. Wordpress automatically creates author pages for users who publish content on a website. We then discovered a Wordpress author page with the username “H_abbasifar.”

Figure 3. WordPress author page on Thaar[.]ir showing username H_abbasifar

We searched the username “H_abbasifar” on Google, which led to an account on Eitaa, a popular Iranian messaging app, with a slightly different username, “H_abasifar.” This profile image of this Eitaa account showed the same logo seen on thaar[.]ir. The account also revealed the full name of the person linked to the account, Hossein Abbasifar (حسین عباسیفر). The Eitaa account also links a related “cultural, artistic, and literary channel” with the username “H_abbasifar,” which has the same spelling as the WordPress user account associated with thaar[.]ir.

Figure 4. Eitaa channel with the same logo used on thaar[.]ir and linking to another account with the same username (@h_abasifar) as the exposed WordPress author page, suggesting a clear link between the platforms.

An archived version of the same Eitaa channel, “H_abasifar,” from October 20, 2022, displayed a different profile photo than the channel’s current photo.

Figure 5. Archived version of the Eitaa channel from February 18, 2022, showing a different profile photo than the channel’s current photo.

A reverse image search of this profile photo on Google surfaced the same photo on a Clubhouse account. This account lists an email, econcul@gmail[.]com.

Figure 6-7 . Clubhouse account associated with @H_ABBASIFAR, which reveals a personal email address

We then connected this email to thaar[.]ir, confirming Abbasifar’s involvement in the website.

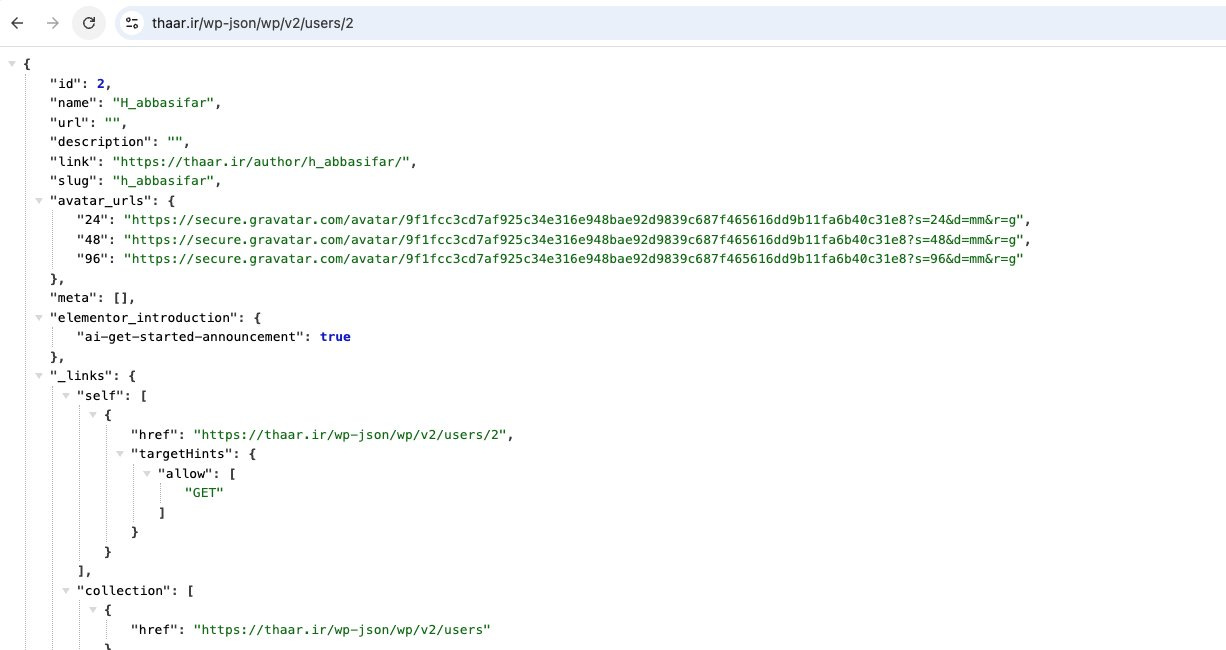

As mentioned above, thaar[.]ir uses WordPress. WordPress includes a REST API that allows various applications—like SEO tools, site analytics platforms, mobile apps, and custom front ends—to interact with the website. Although this API can be fully or partially disabled, or limited to specific endpoints, many developers leave it publicly accessible unless configured otherwise. Thaar[.]ir left an endpoint exposed, thaar[.]ir/wp-json/wp/v2/users/2, which reveals metadata associated with the WordPress author “H_abbasifar.”

Figure 8. Exposed WordPress API endpoint for the H_abbasifar user page on thaar[.]ir, revealing a Gravatar URL containing the SHA-256 hash of the associated email address.

This exposed endpoint reveals a link to the author’s Gravatar profile, an image service that associates a globally recognized avatar with a user’s email address. Gravatar images can automatically appear across platforms such as WordPress, Slack, and GitHub.

Gravatar generates a hash from a user’s email address, which is embedded in the URL associated with their profile. This allows platforms to retrieve the user’s avatar without directly exposing the email itself. Gravatar now recommends using SHA-256 hashing for added security, replacing the less secure MD5 hashes previously used.

The exposed endpoint, thaar[.]ir/wp-json/wp/v2/users/2, reveals the Gravatar URL associated with the WordPress user “H_abbasifar.” The URL contains the SHA-256 hash

9f1fcc3cd7af925c34e316e948bae92d9839c687f465616dd9b11fa6b40c31e8.

While SHA-256 hashes are not easily reversible, they can be “cracked” by generating hashes of likely email addresses and comparing them against the exposed hash. In this case, we hypothesized that the WordPress user “H_abbasifar” may have used the email econcul@gmail[.]com, which is linked to Hossein Abbasifar. Applying the SHA-256 algorithm to this email produced a hash identical to the one in the Gravatar URL, reinforcing the attribution of Abbasifar’s involvement with the website.

Figure 9. Hash value generated from the econcul@gmail[.]com email input, which matches the SHA-256 hash listed in the metadata under the Gravatar URL

We then attempted to find as much information as we could about Hossein Abbasifar, to determine whether he had any official ties to the Iranian regime. Running searches on Google and the online investigation tool OSINT Industries for his email, econcul@gmail[.]com, as well as his usernames, “h_abbasifar” and “h_abasifar,” surfaced many significant results. These include accounts across Telegram, Skype, western social media sites like X and Instagram, and Iranian sites such as Aparat, a video sharing platform, and Virasty, an Iranian X knockoff. Notably, Abbasifar’s LinkedIn account lists his location in New Jersey, potentially providing him a vehicle to pose as a U.S.-based person and approach Americans.

Figure 10. OSINT Industries results for h_abasifar as of July 11, 2025.

Figure 11. OSINT Industries results for “h_abbasifar” as of June 11, 2025.

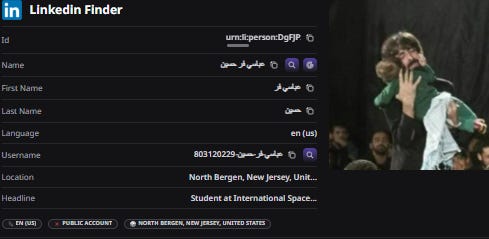

Figure 12. Data associated with Abbasifar’s LinkedIn account, as per OSINT Industries search on July 11 2025.

We also queried Abbasifar’s email using Dehashed, a tool that allows investigators to search data breaches. This search surfaced account details from the 2024 breach of Cutout[.]pro, an AI-powered photo editing and content generation platform. The leaked account included the IP address 5[.]112.76.118, which is registered to an Iranian cellular provider. This supports the assessment that Abbasifar was operating from inside Iran as recently as 2024.

Figure 12. Dehashed result showing breach data associated with econcul@gmail[.]com, including an Iranian IP address associated with his Cutout[.]pro account.

We eventually discovered that Abbasifar at one point claimed to have worked for Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), the regime’s main propaganda network. Abassifar’s Clubhouse account, mentioned earlier, states that he directs an institution called the Seda Media School, and provides a link, heyat[.]school/seda, which is now broken. An archived version of the link from 2021 shows what appears to be a school dedicated to teaching students how to produce and publish audio content including podcasts and radio shows. The site displays lessons taught by “Professor Abbasifar,” which then led us to a 2021 teacher profile for Abbasifar. On this profile, Abbasifar claims that he serves as a specialist at the IRIB’s radio station (صدای جمهوری اسلامی ایران), and that he produces the IRIB program Radio Javan.

Figure 12. Archived copy from September 28, 2021 of Abbasfiar’s teacher profile associated with the Seda School, claiming that Abbasifar works for the IRIB.

As of July 12, 2025, Abbasifar’s campaign continues unabated. Recently he has posted on his Eitaa account encouraging more people to donate to his campaign, which he refers to as Blood Pledge (عهد خون). He also shared a photo of deceased Hezbollah chief Imad Mughniyeh accompanied by Arabic text calling for the complete destruction of Israel.

Figure 13-14. Translated posts from associated Eitaa channel (@h_abasifar) promoting the campaign.

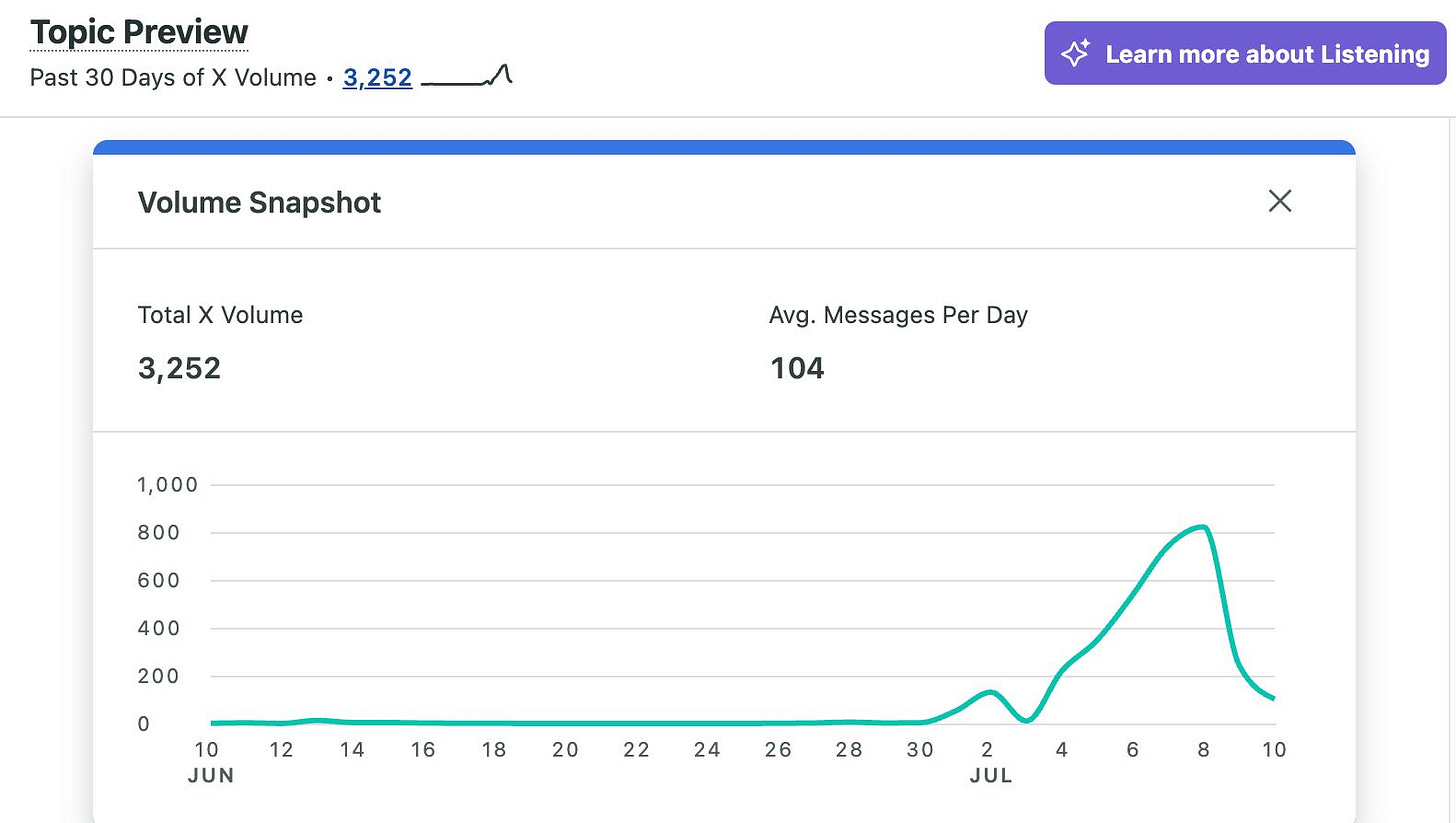

A quick search using Sprout Social’s social listening tools shows that the related hashtag (#عهد_خون) peaked at approximately 800 posts on X just days after the creation of thaar[.]ir. This suggests that Abbasifar’s mobilization campaign briefly gained traction and achieved limited success in circulating on at least one Western social media platform.

Figure 15. A Sprout Social snapshot showing trends in the volume of posts containing the hashtag #عهد_خون on X between June 10 and July 10 2025.

This investigative overview demonstrates how a combination of cyber threat intelligence (CTI) and OSINT can be used to identify malicious actors, including those seeking to mobilize violence through digital platforms. If you have any questions, feel free to contact Ari, who can connect you with me directly.